I took up skating by accident, after watching someone skate the amazing Grapevine move at the Bryan Park last Christmas. I proceeded to buy a pair of ice hockey skates, and learned to properly skate, so I could eventually do the Grapevine.

Every time I learned a new basic skill, I found I could do a part of the Grapevine slightly better. Eventually I understood what skating was all about: the edge, leaning into the edge, the posture, the balance, and most importantly the use of posture to transfer balance from one foot to the other.

This article captures the insight I acquired in this process. Perhaps I can provide fresh ideas on learning to skate, from the perspective of a former outsider. The main thesis of this article is that unlike traditional narratives that describes skating moves in terms of strokes, I think skating can be equally and maybe even better explained as a sequence of falling steps and recovery steps.

Skating as Transfer of Balance

Figure skaters say that skating is all about circles. Hockey tutorials emphasize proper pushing techniques. Both pay attention to edge and turn control. But for me, after a few months of self-teaching from online tutorials, I now think of freestyle skating as fundamentally about balance, leaning, and transfer of balance by leaning from one foot to another.

These are just different ways of looking at and describing the same skating maneuvers. I think they are all valid. But I found that thinking about changes in leaning instead of circles helped me arrive at the right balance required for each move. I found that willing my muscles to move the body from one posture of balance to the next, instead of trying to moves legs to push in the right direction, allowed me to concentrate on the flow of movements.

Skating as Falling and Recovery

Yet another way to paraphrase the transfer of balance is to think of skating as walking. They are both about being in a perpetual state of falling, punctuated by brief instances of a foot making contact with the ground. A foot lands on the ground in order to regain balance and recover from the fall, only to launch the body back into the next phase of falling.

Take counterclockwise forward crossover for example. The traditional stroke-based narrative describes how the right skate pushes off on the inside edge, and the left skate pushes off on the outer edge while the right leg crosses over.

Instead of thinking about the pushes, I find it more useful to treat this crossover maneuver as consisting of two brief moments marked by a skate landing on the ice and balancing the body, plus the acts of falling and recovery that that precede each of these brief moments.

In the forward crossover maneuver, the brief, balanced moment “b1” occurs when the right foot plants down over and in front of the left foot. At this moment the skater’s body is perfectly balanced on the right foot. And if the skater were to freeze her posture at this instance, she would continue to glide forward without falling. The second balanced moment “b2” occurs when the left foot finishes reaching out leftward, and plants down on the ice. Again, if the skater were to freeze her posture at b2, she would continue to glide without falling.

These balanced moments b1 and b2 are clearly illustrated in rare crossover tutorials that start with sideways stepping on the ice, such as these steps, and these steps. The first video illustrates stepping exercises for forward crossover, and the second stepping exercises for backward crossover. But attentive readers will find that the two stepping exercises are identical. And they are both just “walking” exercises where the “walker” can pause indefinitely at either moment b1 or b2, but not between these two points.

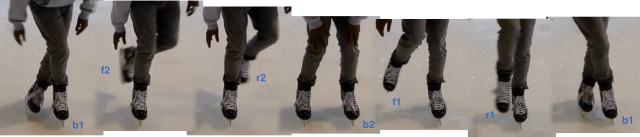

So, what happens between moment b1 and b2, and back from b2 to b1? Take note of how little it takes to turn the above sideways steps into a backward crossover. Watch closely, and see for yourself that no skate is doing any pushing. All efforts are concentrated in moving the non-load-bearing leg out of the previous stable configuration (i.e. b1 or b2), into a state of instability (i.e. falling), then continuing fluidly onward with the same non-load-bearing leg to plant it down into a stable configuration (i.e. recovery). Thus, most skating can be reduced to a continuous sequence of b1, f2, r2, b2, f1, r1, b1, f2, r2, b2… where “b” is a balanced moment, “f” is falling, and “r” is recovery, and the number indicates foot one and foot two.

Why, then, does the skater glide on the ice, when she is not explicitly pushing? Recall the Newtonian law of equal and opposite action/reaction. In order for the skater to move the non-load-bearing leg, the balancing and load-bearing leg must brace and exert force against the ice. In a slow stepping exercise, this force goes largely downward. But in real forward and backward crossover situations, the skater moves in a circle, and the centrifugal force is in play. As a result, the skater leans into the circle to maintain proper balance at m1 and m2. And the movement of non-load-bearing skate toward the center of the circle causes the load-bearing skate to appear to be “pushing” outward, when all it really does is to dig into the ice using an edge at an angle, to gain purchase for the body to flex the non-load-bearing leg.

There is is a similar dualism in juggling. New practitioners tend to focus on “catching” balls, when veterans know that the key is to focus on “throwing” balls right. In skating, it seems to me that instead of asking “where and how I should push with this leg”, one should be asking “where do I need to move that other leg to, and how?” Here is an outside edge drill with no obvious pushing, yet the skater glides on the ice just fine, simply by “walking” the non-load-bearing leg to where he wants the leg to plant down.

And again, in the walking analogy, we almost never think about how to push backward, and instead we think about how to plant the next leg forward. When walking really fast, we start to run. Here the similarity to skating is even more pronounced – what occupies our mind is how to get a firm purchase on the ground with one leg, and how to most quickly move the other leg to plant it as far forward as possible.

So What?

In pure skating, as defined in A System of Figure-skating, Vandervell 1880, one foot and only one foot is skating at any given moment. The “employed” leg is the one shouldering body weight which folks today appear to call the “skating leg”. And the “unemployed” leg is the one off ice which I called “non-load-bearing” earlier, and folks today seem to know as the “free leg”. Traditional narratives teaches skater how to deploy strokes on the employed leg. But I argue that one should instead focus on moving an unemployed leg through the body falling, recovering and finally regaining a brief moment of balance.

I try to concentrate on making the unemployed leg land in perfect balance. To do this, the skater needs to move hands, shoulders, the hip and legs in such a way as to transfer weight and momentum from one balance moment to the next balance moment. When the unemployed leg plants down on the ice, it needs to hit the right spot with the right leaning, and become the new employed leg without causing the skater to lose balance. The previous employed leg has executed its pushing duties which came naturally as a reaction to the trajectory of the unemployed leg, and to the body falling then recovering. The previous employed leg now becomes the new unemployed leg. And the cycle repeats.

Even thought it may seem unintuitive, one can apply the same falling/recovery analysis to “non-pure” skating moves such as the Grapevine. Even though the Grapevine is skated on two feet, the same principle of falling and recovery still govern the move. If interested, read on: Learn to Skate the Two-foot Grapevine Analytically.

Update 2022-04-28: I have since elaborated on the same falling/recovery nature of skating in yet another post. This time it’s about inline skating, not ice skating. But the same principles apply. See: How to Inline Skate.

Could this falling and recovery on the unemployed leg help a stroke victim recover his balance by using his unemployed leg (his stroke leg) in fall and recovery movements to regain his balance on a leg he is unable to plant down for fear of falling and thus preventing him from walking.

Am not a doctor, Susan. Perhaps a therapist would know this better. It seems to me that a phisical therapist will know the sequence of falling and recovery in a walking gait a lot better than I found myself by a quick research when I wrote this article. I would practice on carpet or mat though… not on the ice.

What an interesting analysis to ice skating! What you said about thinking as skating as walking was really interesting. Whenever I ask advice from a skater on how to skate well, they always say that it’s similar to walking. I can definitely see what they meant by that now.

Hey… Taylor. I just realized that I never did reply to your comment. Thanks for the comment on this analysis. Yeah. Experienced skater also casually told me that skating was like walking.

When I first started to teach myself skating, like all beginners I took this to mean that I would deploy the same walking pattern on the ice, without knowing about using the edge of the blade to dig into the ice. You know that doesn’t work.

Then I learned to push properly and to stop thinking of this as walking.

But in the end I understood how to reconsider skating as a walking exercise. It appears that I came full circle :)