On a windy and rainy day in November, I rented a kayak from Go Bananas, and drove to He’eia Kea Boat Harbor. I launched off towards where I thought the legendary Kaneohe Sandbar would be.

For the entire trip to the sandbar, I paddled alone in a foreboding ocean. Perhaps “bay” is a more accurate description. But from my low vantage point, it looked as if I were in the middle of the wide wide sea under dark clouds. I aimed for Kapapa Island as told. And that was good advice. Because from my kayak, all I could see were breaking waves in every direction, except for that tiny speck of an island in the distance.

I kept turning my kayak back towards the harbor, second-guessing the sanity of my choice. I saw dark clouds pouring rain over entire towns. I pivoted back towards Kapapa Island and paddled some more, all the while frightened to the core and utterly alone.

I reached the last boat in sight, hoping to find tourists having a great time. But it was empty, silent and moored in deep water. No sandbar to be seen. I swung back facing the harbor. I again turned towards Kapapa. I kept going.

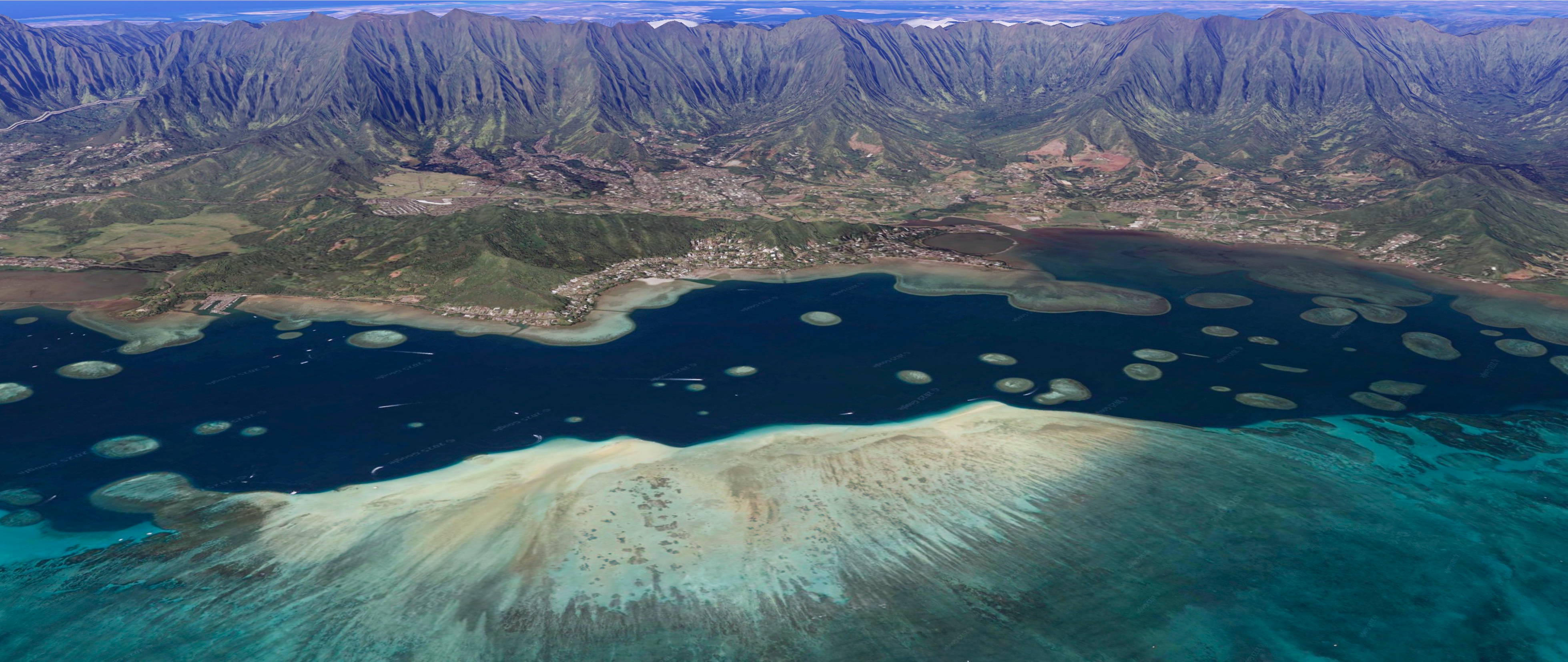

After what seemed like a lifetime, I sensed a change in water color. Shortly the sun poked its head out from behind clouds. And magic happened. The sea all around me turned turquoise as soon as sunlight touched them, revealing that I was merely a foot above the sand now. I got why this place is also known as the Sunken Island.

I paddled around and found a lone standup paddler lying supine on his board, drinking from his flask. I also ran into a birthday party seated around a half-submerged table. Then Captain Bruce showed up, unloading a bunch of merrymakers who were blissfully unaware of the hardship some went through, to find and reach this sunken island.

Now that I know the place, I won’t have any trouble coming back and finding it again. Looking back, I can’t help wondering why I expected an immense sandbar rising above the sea, even though I knew it was high tide. Not being able to find anything jutting out of the dark water really did frighten me.

Then it hit me.

Have you ever seen a picture of the immense sandbar under dark water with the sun behind clouds? Nor have I. That doesn’t quite capture the vacation spirit. Instead you see tourists enjoying the best time of their lives, playing makeshift volleyball on an exposed sandbar under a blue sky.

I created two illustrations based on Google Earth to show you the Kaneohe Sandbar at low tide, and then its alternative personality, the Sunken Island at high tide. Yes, you can still see the sunken island at high tide from a helicopter. But the “island” really does disappear beneath dark waters at high tide without direct sunlight, as seen from the low vantage point afforded by a lowly kayak. I wish someone had written this post before my trip. Sigh.

Read on, if you plan to visit this sunken island. Here’s essential information for a safe and enjoyable trip.

- Where to rent kayaks

- Where to launch kayaks

- Paddling route to the Sunken Island

- From your kayak’s perspective

- Fear of the unknown

- Apparent distance of sandbar and Kapapa

- Weather, surf and tide

- Just how deep is Kaneohe Bay / Sandbar

- Miscellaneous pictures and videos

Where to rent kayaks

In the past you could rent kayaks on shore around Kaneohe Bay, including at the Heʻeia State Park. According to Love O‘ahu, sea vehicles can no longer be rented within 1000 feet of the shoreline after March 2024. So you will need to rent kayaks elsewhere and transport them to Kaneohe Bay.

Some tour boats will take you to the sandbar and give you a standup paddle board or a cheap kayaks to play with. You may find it convenient. It’s an alternative to paddling out from shore under your own power. But that’s not what this post is about.

If you continue reading, I assume you are not a first-time kayaker. You likely know how to paddle properly. That is, you derive power from leg drive and torso rotation. Your shoulders and arms never pull but gently help with a slight top arm extension (push). An undeviated line from boat harbor to sandbar already measures 1.25 miles. You know how to kayak without hurting yourself, for more than twice that distance in order to come back ashore safely.

I was told that decked kayaks weren’t a thing in Hawaii; the ocean was warm year-round. You’ll thus find sit-on-top models for rent here. I recommend long touring kayaks with a skeg or a rudder. Do not rent a short recreational kayak. There will be wind, waves and currents; you will have a greater time when your boat tracks straight by itself.

Rent from a reputable store somewhere on the island. It doesn’t matter where you rent it – drive it for 2 minutes from town to the bay, or for 20 minutes across Koʻolau Range on Likelike Highway. Either way, you’ll spend more time securing the kayak to, and then unloading it from your car.

I rented from Go Bananas. The store is located at Waikiki on Kapahulu Avenue, where you find all of the good food, including Leonard’s. Talk to John. He’s been kayaking for 30 years. His business helps local folks have a great time without having to store their own kayaks. His ear pricked up when I told him I had brought my own high-back kayak life jacket from the mainland. A lovely conversation on kayaking ensued. Eventually John said instead of lingering around Waikiki, I should head straight to Kaneohe Sandbar. He showed me his sandbar photobook to help me understand the trip.

Pay attention when John explains how he secures a kayak to your car. Likely you are renting an unfamiliar car. Some cars require particular strapping techniques. He showed me how not to break the immense sunroof on my rental. For the record, I rented a compact. They were going to give me a Kia K5, but ended up giving me this monster of a car. That’s a story for another time.

Where to launch kayaks

In the past, folks rented kayaks at the Heʻeia State Park and launched directly from the park. It’s not clear whether kayak rental is still available in 2025, as an exception to the non-commercial rule mentioned at Love O‘ahu, Nevertheless, the park can still be used to launch kayaks, with a boat ramp on each side of this small peninsula.

You won’t find much information about this park online, not even on its official site. Earlier in our trip we stumbled upon this park on the way to check out Paradise Bay Resort. I took this picture at the park without giving it a second thought. It turns out to be more useful than most things you find online.

I didn’t know that the park would be closed on Mondays. I came back on a Monday to launch from the park, only to find the gate chained up, with a hanging sign that said park closed. Now you also know.

But it was fine. There is a public launch site by the Kaneohe Canoe Club, next door to the state park. You won’t find this club on Google Maps. The club is officially known as Kaneohe Outrigger Canoe Club. And they launch from a boat ramp by the entrance to He’eia Kea Boat Harbor.

For particular reasons I had to leave the kayak here briefly. I moved my kayak into the hut.

In retrospect I probably trespassed. A very dumb mistake. I also launched from behind that hut. More mistakes. I don’t know why I missed the boat ramp when unloading. I only discovered it when I paddled back. I must have been blind.

Paddling route to the Sunken Island

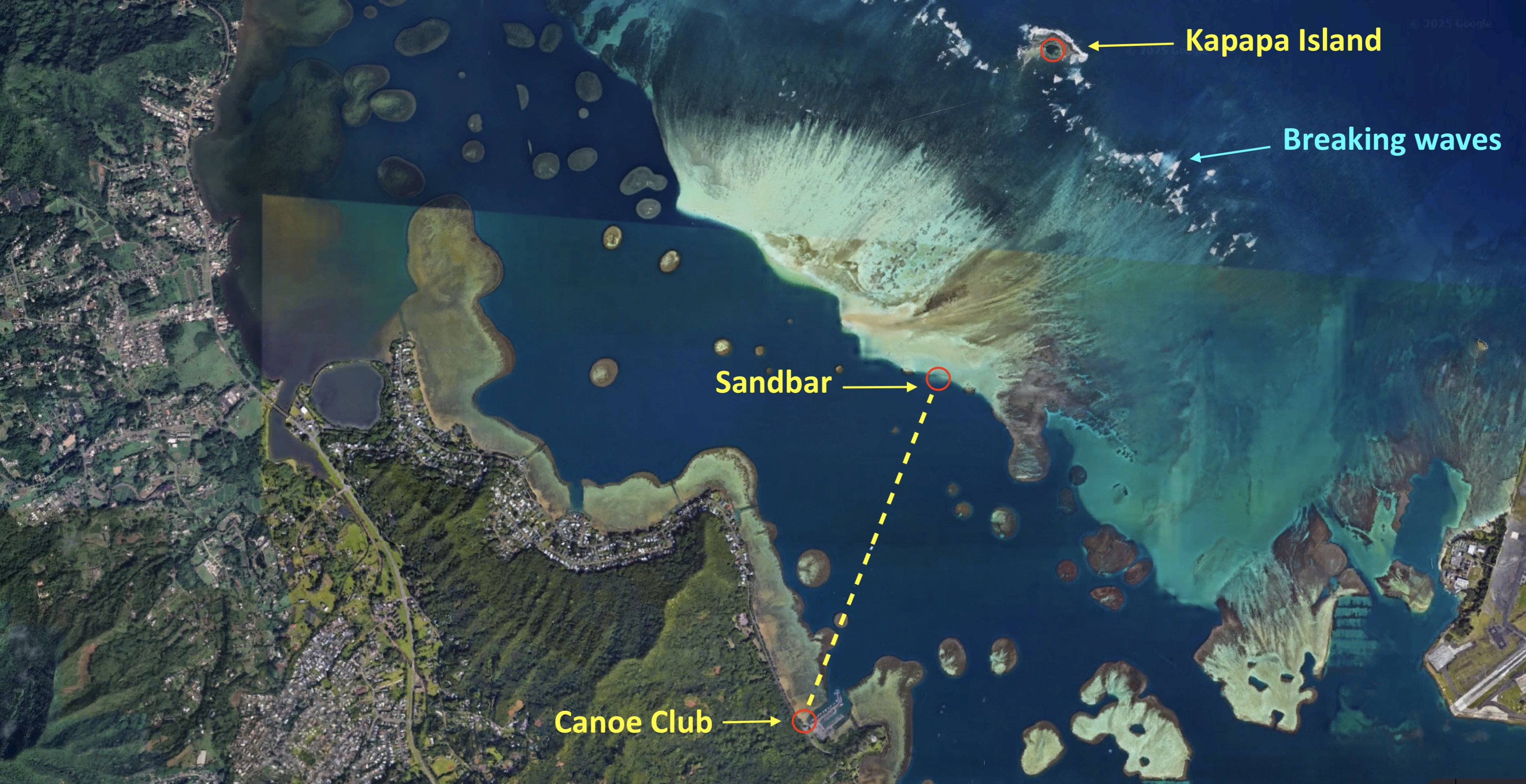

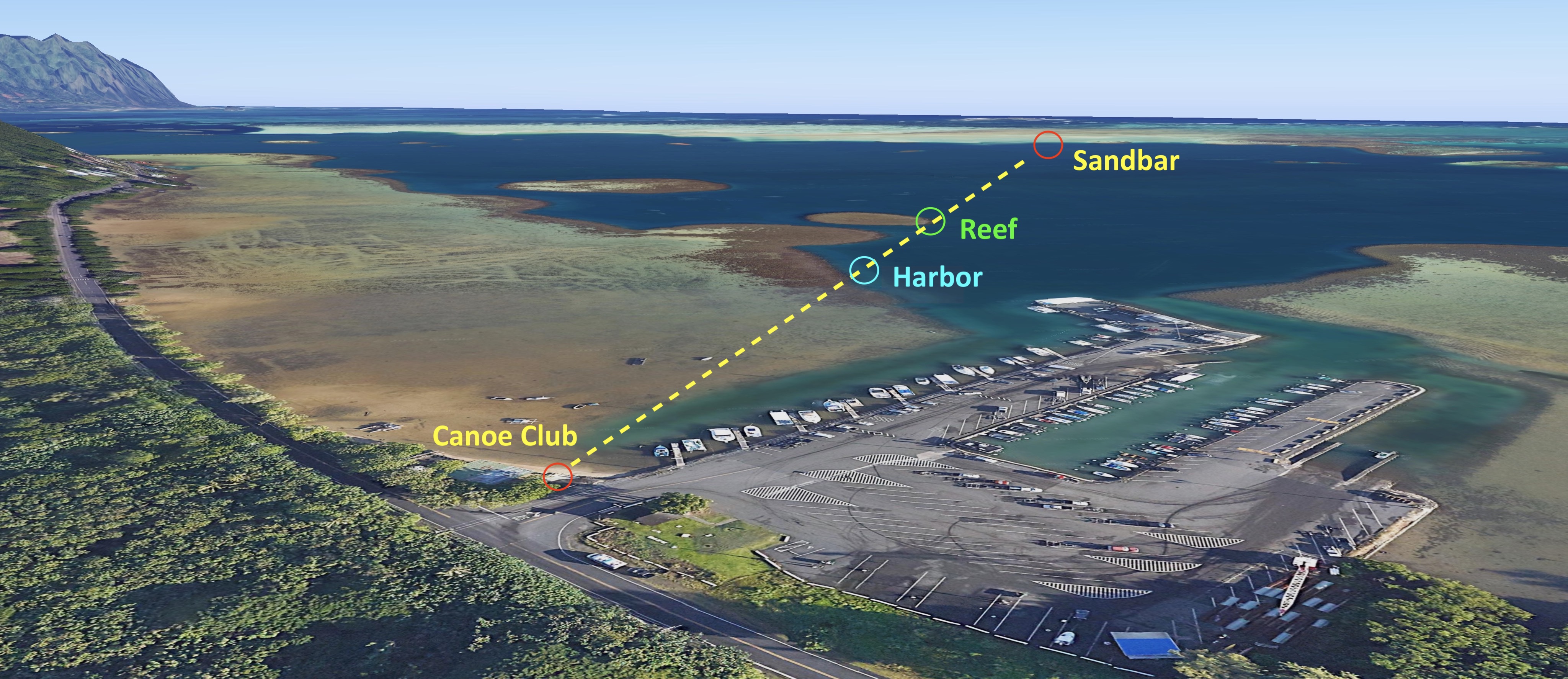

I made an annotated map of the Kaneohe Bay, showing key landmarks you will see from the water. The dashed line indicates a route from the Canoe Club to an edge of the sandbar, measuring roughly 1.25 miles.

Identify these landmarks as you examine pictures and videos from this post. The Kualoa mountain range demarcates one end of the landmass you see from the water. The Marine Corps marks the other end of the landmass, situated on the Mokapu Peninsula.

A close-up view shows this route further leading to Kapapa Island, a bird sanctuary, if you continue paddling onward past the sandbar for another 1.25 miles. Click on this link to see the same view in 3D on Google Earth.

From your kayak’s perspective

The following video gives you an idea of the view to expect out there, captured from my kayak just before I reached the sandbar. The sun was still behind the clouds. I looked back towards the shore and saw entire towns being rained on.

Looking out from the Canoe Club towards the Pacific Ocean, you will first see boats. While appearing to be far away, they are actually moored very close to shore, in the grand scale of things. These boats seem to be half way between you and an island. But that’s an illusion. That’s Kapapa Island, and it’s actually 2.5 miles away from you.

In comparison, the boats are moored not far beyond the end of the marina seen on the right. Replicate this 3D view on Google Earth.

At times you may observe a likeness of tapered landmass extending out from Kapapa Island in both directions, especially when loitering on the calm water above the sunken sandbar. What you see around the island are breaking waves at the distant edge of the sandbar. In that direction, there’s no landmass except for that small island. And did you notice that Kapapa island still looks about the same size as before, even thought this picture was taken exactly half way from shore to the island? Replicate this 3D view on Google Earth.

Fear of the unknown

I mentioned my naive expectation to see a sandbar rising above water at high tide. I grew scared when failing to find it after a long paddle. Some of you are sharp. You are like, “but why didn’t he look at his Google Maps?”

I kept my phone in a cheap waterproof bag, and I took it out to take pictures when I felt safe at sea – one can’t get clear images through a thick plastic bag. You’ll see a paddle strapped under bungee cords in most pictures with the kayak in sight. John didn’t give me an extra paddle. I had to put my paddle away every time I took a picture – I wasn’t going to risk dropping my phone from a single hand.

I took this picture of the last boat I came across. I soon realized it was not filled with merrymakers; it was empty and silent. And I did not find an immense sandbar behind it. Panic set in.

I looked at my phone but didn’t believe where it said I was. After all, we’ve all experienced GPS inaccuracies when driving close to a body of water; and now I was completely engulfed by water. I was still aiming for Kapapa Island, as can be seen in the picture above. But now the wind blowing past me felt ill-intentioned. And the waves – oh, they started to scare me. I felt the weight of the deep ocean beneath me now.

For the next 20 minutes, I took no pictures or videos. I was compelled to focus all my attention on steering into waves lest they flipped my kayak sideways, even if I routinely paddled into bigger waves in the past. I tweaked the rudder to counter fickle winds lest I got blown off-course, even when my own paddling caused these heading deviations. Then I turned back for the boat harbor. Then I steered back towards Kapapa. But I have already told you that.

Finally, I sensed a slight change of colors in the ocean, as the waves died down. This was when I felt comfortable enough to take my phone out again. I took the picture used at the top of this post.

Apparent distance of sandbar and Kapapa

This experience got me thinking. I had never felt lost at sea before. But then I had never kayaked alone this far away from shore. Most of my sea trips hugged a coast where my forward progress could be confirmed by looking ashore. And whenever I was far away from shore, I was with a group – I just followed the leader.

I was grateful that John drilled into my head: “aim for Kapapa”. I kept thinking at the moment that I couldn’t miss the sandbar if I tracked a straight line toward Kapapa. But slowly I accepted that perhaps the sandbar was completely submerged. And possibly I had already sailed over it. Without direct sunlight it was hard to confirm, looking at that dark water. I honestly did not know how deep the sandbar could sink under waves.

And I still don’t know where that last boat was moored. I think it was just beyond the reef in the next image. If the sandbar was exposed at low tide, and if one were to look from the canoe club, that boat would have “appeared” to sit just in front of the sandbar. Recreate this view for yourself on Google Earth.

But in fact that reef is still a long way from the sandbar. The real distance between two waypoints can only be visually reasoned about without a sextant and the like, if both lie roughly equidistant from the viewer. See this view for yourself on Google Earth.

Judging by the timestamps of my pictures, it took me 25 mins to paddle from the sandbar back to the canoe club. The return trip was executed without hesitations, unlike my outbound trip. The return more or less traced a 1.25-mile straight line between the two waypoints. This translates to an average speed of 3 mph, which tracks with my past experience. The trade wind at about 45° angle behind my back did push me towards shore, but also blew me off-course towards Kualoa. I don’t know whether the wind influence was net positive or negative.

Next time, I will probably chart out waypoints and distances ahead of time. Compensating for wind and current, I can likely use elapsed time to figure out my location assuming a constant paddling speed.

Or, perhaps I can simply carry a nautical device like a sane person would. Failing that, I can probably get a quality waterproof case with real touchscreen support for my phone, like normal people do… and unlike the white pouch I bought for this Oahu trip.

If you are curious about apparent size, aka angular size, check out this YouTube video.

Weather, surf and tide

This island, like other Hawaiian islands, has got a multi-climate personality, due to its NE trade wind and its mountain ranges. The side of the island you are on will largely determine the climate you experience. But it’s got microclimates too. Sometimes the same cloud rains on your town, but not the next one over. You’ve seen such microclimates in effect earlier.

Here is another one. You are looking at almost all of Waikiki plus Ala Moana. Zoom in and look at the dead center. See that faint rainbow, and then the neighborhood being rained on. Note how the entire beach shoreline is under sunshine however? Welcome to Hawaii in November.

I was there at the beginning of the rainy season which starts in November and ends in March. I did not experience a clear blue-sky day at Kaneohe nor other windward towns. That’s not to say that the sun never come out from behind the clouds. But my experience at Waikiki was noticeably different. The sun was out more often than not, and it rarely rained at the beach. The leeward side was even sunnier.

One benefit of visiting during the rainy season is that you find rainbows all the time. Sometimes they were faint, and I only noticed them while processing pictures at home. Invariably I found a rainbow in every picture taken with the sun at my back. In a few, I caught rainbows so bright and saturated they looked unreal. They don’t call Hawaii the Rainbow State for nothing.

As for Kaneohe Bay, I rarely saw sunshine during this kayak trip. Those tourists on Captain Bruce’s boat were very lucky. They arrived at the sunken island just in time as the sun came out. Even then, often parts of the sandbar were under clouds.

The Windy app from windy.com is an essential tool. I paid $30 for a one-year subscription, just for this trip. Having hourly hyperlocal forecasts and historical satellite views at my fingertips was well-worth the money. This is also the consensus on Reddit. I learned much about visiting Hawaii from the r/VisitingHawaii wiki.

Folks here universally rely on surf reporting from SNN, the Surf New Network. It’s a Hawaiian thing. John from Go Bananas checked the surf report the day before, and on the day of the trip again, before he would let me rent a kayak to paddle at Kaneohe Bay. Waves here are no joke, despite exceptions such as Waikiki where surf is generally not an issue for the average person.

I run an ancient and simple app by 7th Gear called “Tides” on my phone. It is easy to use… not that ease-of-use helped me much, when I failed to research beforehand. I didn’t know how much of the sandbar remained above water at high tide. Now I know. None of it remains above water at high tide; the sandbar is covered by several inches to a couple of feet of water. That is, knee-waist deep. It is only exposed from mid tide to low tide.

Just how deep is Kaneohe Bay / Sandbar

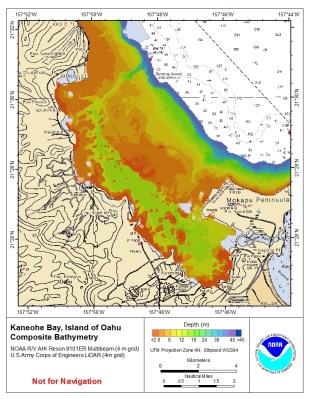

I kept asking myself after this experience, just how deep is the bay?

Mainly I wanted to understand whether that feeling of being at sea was real, or just an imagination when I merely paddled in shallow water.

But of course, this was not a simple question. The bay has an unusual, rectangular shape, with an immense sandbar taking up half of its volume in the middle. One must treat the bay as a whole comprising several parts with different nautical features.

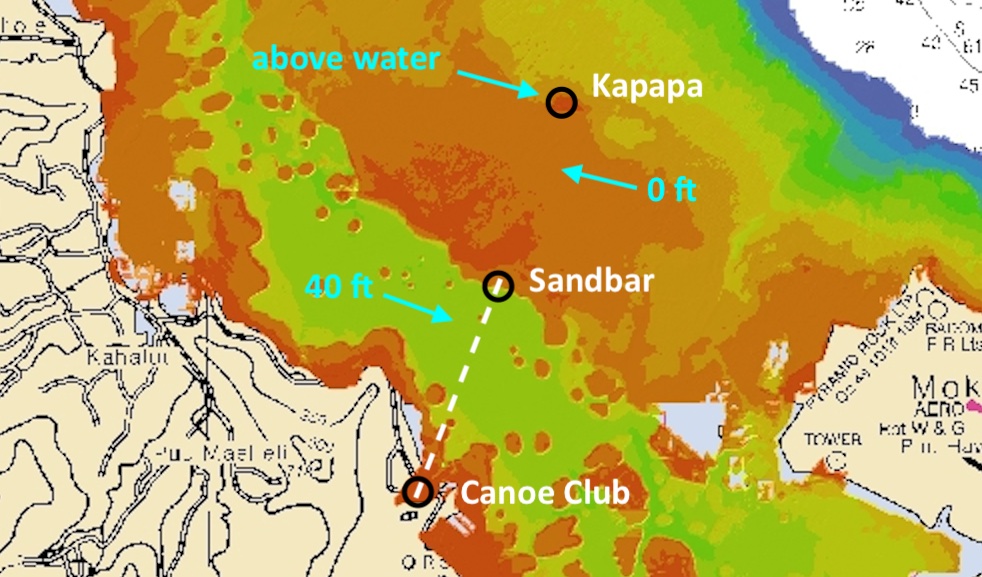

I looked for depth maps showing contours of the underwater landscape. Here is a Kaneohe Bay bathymetric chart I found. This was synthesized from 4m-grid LiDAR surveys conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2002 and 2007.

On the following inset of the bathymetric chart, I have annotated the paddling route to the sandbar. According to the legend, that “vast ocean” I crossed measures just just 40 feet deep, or 12 meters. It’s just deep enough for a modern-day cruise ship to sail through.

Bathymetric chart is a useful tool for mapping out underwater landscape for studying marine life, for instance. But one should not rely on a it for navigation. For navigation, one must turns to hydrographic charts, or nautical charts, with annotations required for navigation planning, including ship channels, buoys, and underwater hazards.

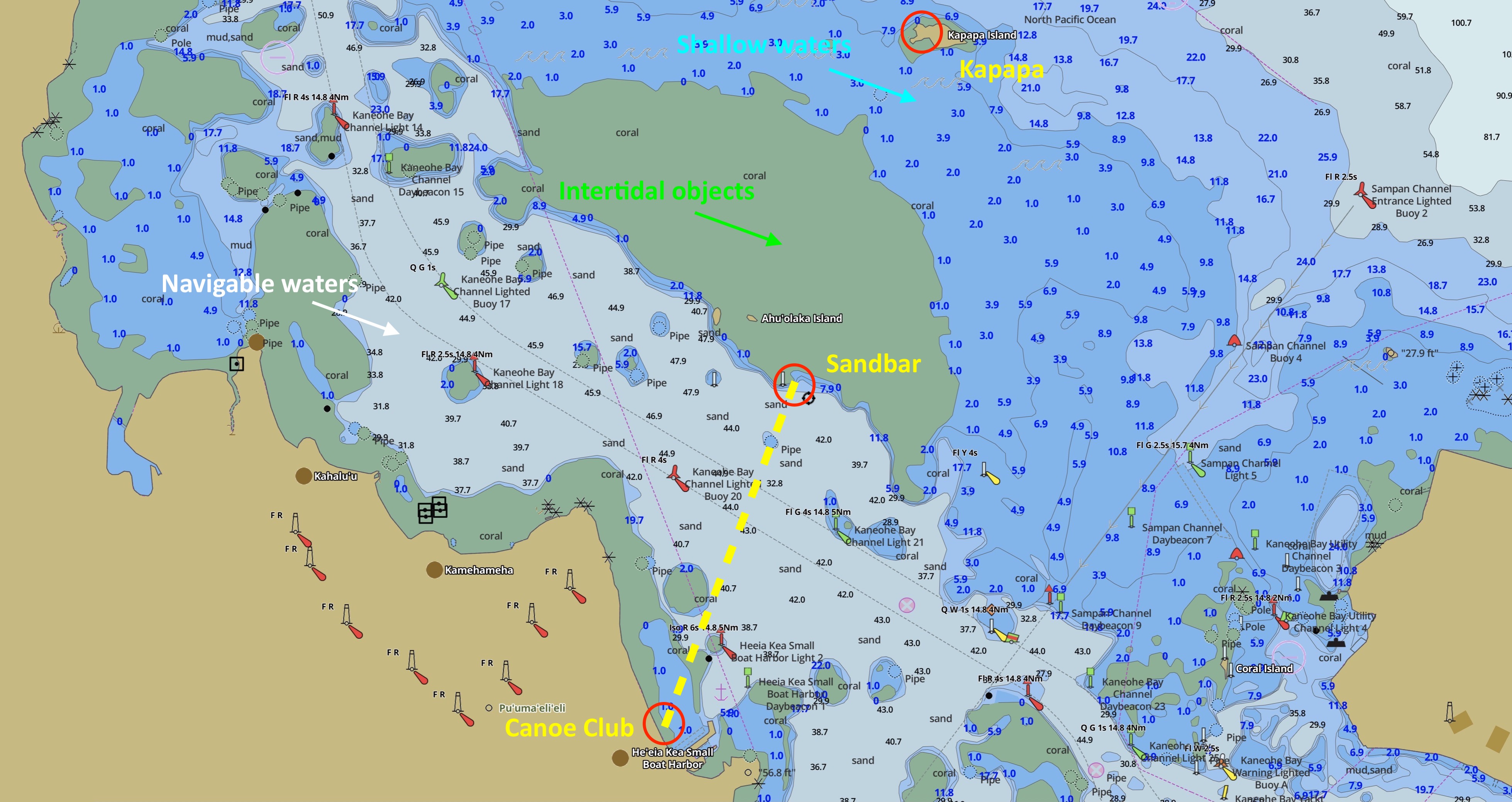

Following is a rendering of the NOAA Nautical Chart 19359, showing O‘ahu East Coast and Käne‘ohe Bay. Note that printed charts have been retired; they are no longer updated and should not actually be used for navigation. The screenshot is from an interactive version of the chart provided by GPS Nautical Charts.

Modern ECDIS chart can be configured to show contours, colors and hazards based on your boat’s particular specs. Here I simply used a default configuration. Consult the so-called U.S. Chart No. 1, a 134-page document, on ECDIS symbols and annotations.

In general, bodies of water tinted white on a chart are deep enough and free of hazard to be navigable. In this particular screenshot, navigable waters between the canoe club and the sandbar range from 30ft to 45ft deep. A designated navigation channel averaging 40ft cuts through the waters, running parallel to the entire length of the sandbar. This channel starts at the north end of the bay for returning ships, and ends at the marine base, with green and red buoys on each side.

Blue tints indicate waters that are potentially hazardous to a large ship. This usually indicates shallow water and other underwater obstructions such as rocks and ship wrecks. On this ECDIS chart, waters between 1 foot and 30 feet are configured with a blue tint. For us poor kayakers, blue waters may as well be treated as navigable. But do watch out for hard rocks and reef that may scratch your boat at low tide.

Features that always stand above water regardless of tides are brown. That’s land.

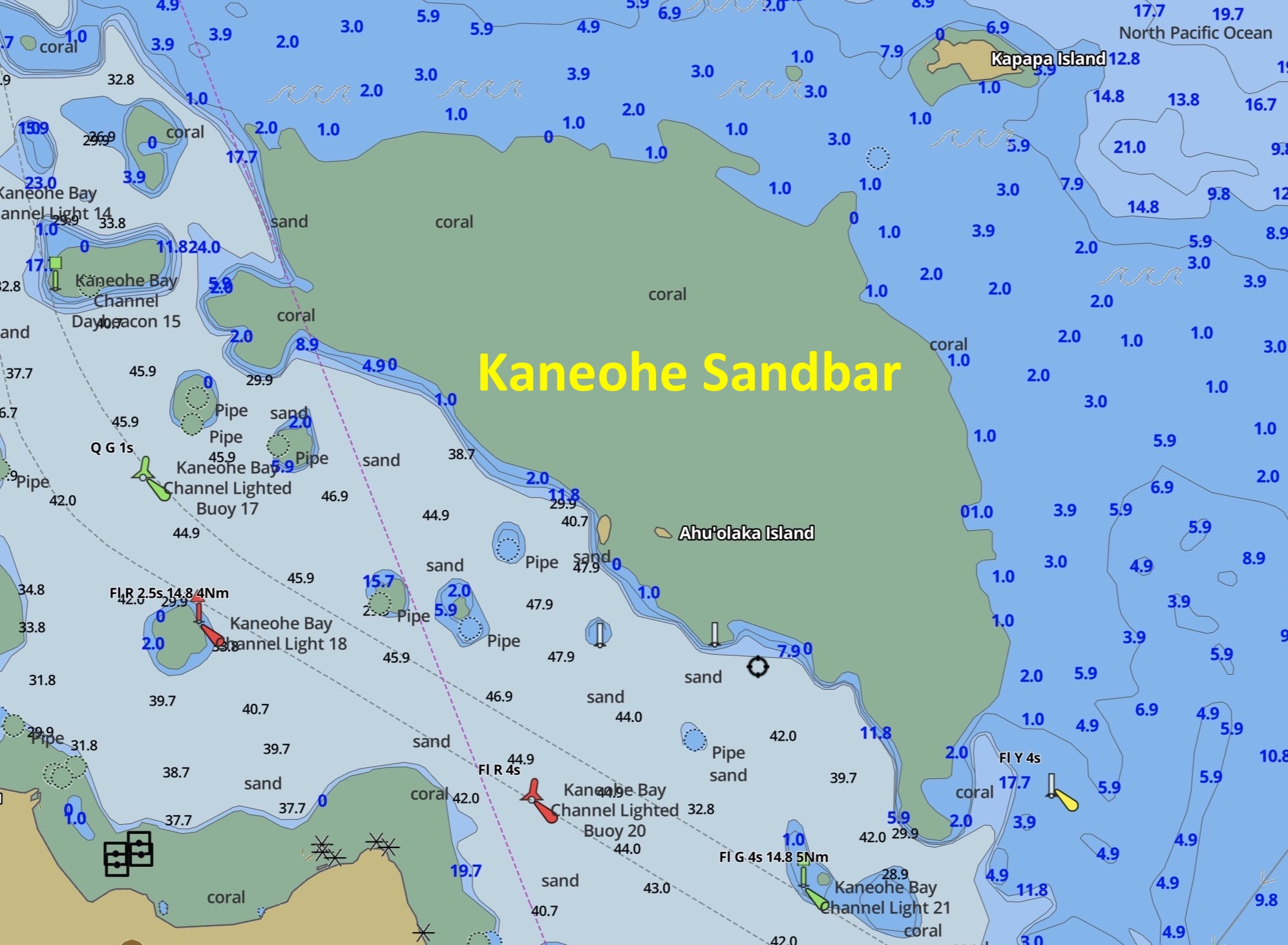

If you are still reading… well, I saved the best for last. See that large blob of green in the middle of the bay? I’ve replicated it below for you. Green tints in ECDIS indicate “intertidal” shoals. These areas appear exposed or sink under water depending on current tidal conditions.

So, if an area is marked green, and not brown, then it will disappear from view at some point in a tidal cycle. So there you have it, the whole Kaneohe Sandbar does disappear under at least 1 foot of water at high tide, according to the chart.

Or does it?

This retired chart does show two brown spots within the sandbar which presumably always sat above water. But I haven’t seen them in my quick exploration. Perhaps sands shifted. Perhaps I simply haven’t paddled close enough to see. Maybe you’ll find them.

Miscellaneous pictures and videos

There are more green-tinted areas on the nautical chart. Many of these are reefs of some kind. Except for a deep navigation channel carved out alongside its marina, the boat harbor is surrounded by a mixture of sand and reef. This is what it looks like off the boat ramp.

By the way, before I paddled out in full-force, I turned around to look at the harbor and identify landmarks. When paddling without navigation aids, one quickly looses sight of specific land features, as everything on land shrinks and merges into the horizon. As I paddled away, I kept track of tall boat masts in the harbor and electric poles lining the shore road. This allowed me to fix on the right landmark when returning.

When the sun came out, shadows of clouds retreated at an incredible speed. It caught me unprepared in this video. You have seen earlier two screenshots taken from it.

I found a lone standup paddler lying supine on his board, drinking from his flask.

Then I ran into a birthday party seated around a half-submerged table.

All sorts of aircraft take off and land at the USMC base. Here is a KC-130J tanker banking above the sandbar to line up with the runway as it landed.

Some more pictures of the happy crowd from Captain Bruce’s boat.

I’ll end this long treatise on a happy note with this video. Be safe paddling.