You know UV rays from the sun burn your skin and damage your eyes. So you apply sunscreen and put on sunglasses before you head out. Sunscreen bottles usually come with an SPF number (Sun Protection Factor). But your sunglasses usually carry no indication of its effectiveness. When your sunscreen fails, you know right away within the hour – simply look at your skin. But when you wear sunglasses that fail to block UV rays from reaching your eyes, you only find out years later, after your ophthalmologist tells you that you have already developed cataracts, and suffered cornea and/or other permanent damages.

How do you know your sunglasses actually block out all UV rays? The best and the safest way is to walk into your local eyeglass store. They will usually check your sunglasses for UV protection, for free. It takes only a few minutes.

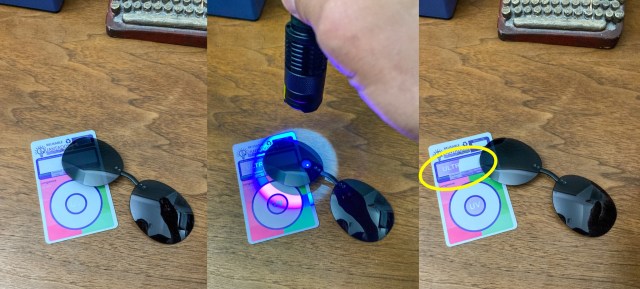

But you are reading this article. So obviously that isn’t how you roll. You want to check and confirm that your glasses block out UV rays, on your own, in the comfort of your own home. Following picture illustrates the basics of a procedure for just that.

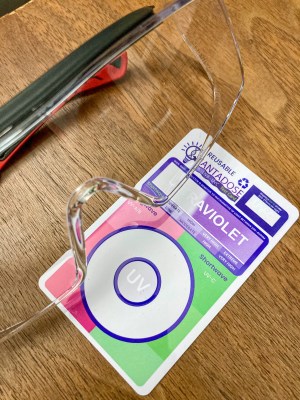

All you need is a proper UV flashlight and a proper UV tester card. If your sunglasses block out UV rays, the test strip at the top will only turn purple, where the strip is not covered by your sunglasses. Watch this video clip:

But this simple procedure invites more questions than it answers.

For instance, how do I know that the UV flashlight is representative of the UV rays I get from the sun outdoor? After all, there are UV-A, UV-B and UV-C. The flashlight may be emitting only one of these types. What if the flashlight emits only visible and harmless blue light, and the test strip is instead just reacting to shortwaves in the visible spectrum?

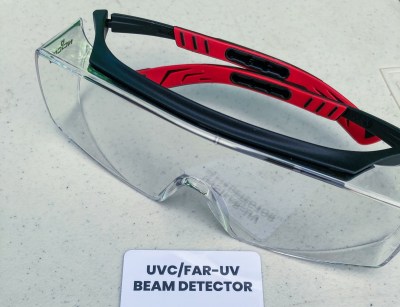

Suppose the flashlight does emit UV rays. How do I know my eyes are not being damaged looking at the UV light reflecting off the tester card? Ah, OK. I should wear a pair of safety goggles certified for UV400. But if I wear these goggles and they actually block out all UV lights, then how do I see the card react to UV rays from the flashlight?

The Short Answer

UV-A (315nm-400nm), UV-B (280nm-315nm), and UV-C (100nm-280nm) all cause damages to a person. Many sources generate these UV rays, but in general you wear sunglasses to protect against UV rays from the sun. While the sun emits all three types of UV rays, the ozone layer and the atmosphere completely absorb and block out UV-C, before it can reach you. So we don’t even need to worry about UV-C.

Common glasses (e.g. soda–lime glasses used in windowpanes) block out all UV-B and UV-C rays. Thus, by default you are shielded from UV-B behind a car window, or behind glass spectacles. This takes care of UV-B.

That leaves only UV-A for you to worry about. That’s where the UV flashlight comes in. It emits a UV band concentrated at 365nm (UV-A). It also emits some visible blue light (400nm-450nm) which is helpful for aiming and focusing the light cone, as UV-A is not visible. You use this UV flashlight to simulate the sun, when you can’t get direct sunlight to beam down on you, unfiltered by cloud.

It turns out you can get a cheap but reliable UV tester card that reacts to UV rays. These temporarily alter the molecular structure of a layer of photochromic ink, such that the layer now absorbs some bands of visible rays more than other bands. In other words, once a layer reacts to UV rays, it looks tinted to the human eye for about 15 seconds, even after the UV source is removed.

So you simply cover a part of the test strip with a spectacle of your sunglasses, and shine the UV flashlight on both strip and glasses for 10 seconds. Turn off the flashlight, and remove your sunglasses. If the test strip turns tinted (purple in the card shown earlier) where unprotected, and remains untinted (white in the card shown earlier) where covered by sunglasses, then you know your sunglasses block out UV-A completely.

Most inexpensive UV tester cards can only indicate the presence of any UV rays this way, but cannot distinguish between UV-A, UV-B and UV-C. Some cards can distinguish between UV-A/B and UV-C using a different mechanism (e.g. the two concentric circles), but even those can’t tell UV-A apart from UV-B. If you conduct this experiment under direct sunlight instead of a UV-A flashlight, then you can’t actually be sure that an untinted white part of the test trip is an indicate that both UV-A and UV-B rays are blocked out by your sunglasses. Perhaps the test strip doesn’t even react to UV-B at all (unlikely though).

As mentioned, soda-lime glasses block out UV-B completely. But many sunglasses are made of other materials, including acrylic, polycarbonate, triacetatate cellulose (TAC), and anything else irresponsible manufacturers get their hands on. Not all of them inherently block out UV-B. I don’t know, for instance, what material my clip-on sunglasses are made of.

So I don’t actually know how to test for effectiveness of UV-B filtering. And I can only trust that if a pair of sunglasses are explicitly made to block out 100% of UV-A, then it will also block out UV-B.

In the beginning I was wary of staring at UV light produced by the flashlight. I bought a pair of ANSI Z87-rated safety goggles, to wear over my prescription glasses. These safety goggles blocked out all UV rays, just like my sunglasses. But they were clear, so they didn’t affect my color perception. I was able to interpret color (hue) changes on the tester card accurately, while wearing them.

After a while, I found that the UV flashlight produced roughly the same amount of UV-A as the sun, at noon on a cloudless day. The flashlight cone of the diameter shown turned the test strip purple as fast as the midday sun. A back-of-the-envelope calculation confirmed that the flashlight produces UV-A wattage output in the same order of magnitude as the midday sun, when I focused the flashlight output narrowly as shown. This seems to indicate that the invisible UV-A reflecting off the tester card from my flashlight cannot do more damages to my eyes, than a midday sun can, were I to conduct these experiments without safety goggles.

The Long Answer

I’ve done a bunch of experiments, and have taken a bunch of pictures. I did these because I didn’t initially find easy answers online, to help me understand various aspects of UV testing. One day I may yet write answers to all of those questions.

For now, here are some fun facts:

My clear prescription glasses do block 100% of UV-A, as they were advertised then. I also tested those clear safety goggles – they too block out all UV rays. But a normal piece of clear glass can, on the other hand, colors the test strip entirely purple – it lets a majority of UV-A rays through.

Clouds do significantly reduce UV-A rays. See how much slower the test script turn purple when cloud obscured direct sunlight.

I can’t detect any UV-C from any lamps from my house. I can’t detect any UV-C from the sun on a cloudless day either. The ozone layer is doing its job.

You can detect counterfeit dollar bills by shining the UV flashlight on them. Use the UV tester cards to check for proper shielding of halogen lamps w.r.t. UV-A, UV-B and UV-C.

Trying to take a picture of the UV flashlight acting on a tester card is not the most straightforward task. The UV rays clearly mess with the camera sensor and/or software on my phone. Sometimes they ting the entire card blue. But at slightly different reflection angles the camera shifts its color balance profile.

The center circles are a “three-pigment UV analyte”, whatever that means. But it seems like these pigments react instantaneously to UV rays. When no UV is present, they reflect all visible light, thus the circles look white. Product info claims that circles grows red/pink with this peak range: 325nm-385nm (solidly UV-A only). I managed to capture this effect reliably in video mode, at certain angles. As soon as the UV source is removed, the outer circle turns white again. I can’t confirm the claimed green peak range of 222nm-275nm (solidly UV-C only).